Contrarians can teach the world valuable lessons

A feature story I wrote for The American Conservative about 'Jeopardy!' whiz James Holzahauer shows benefits of trying a different approach. Also, Troy dispatches USM, play at home again Thursday.

Author’s note: Today, I decided to run one of my first freelance articles that was actually published by a fairly well-known national publication, The American Conservative, several years ago.

The subject might seem strange. The story is about “Jeopardy!” sensation James Holzhaurer, but the story is really about the power of thinking outside the box.

As someone who often questions authorized narratives, I’m intrigued by mavericks who were bold enough to try something a different way.

At the end of the story, I added a few mavericks from the sports world.

***

For all practical purposes, the way Jeopardy! is played hasn’t changed much since Art Fleming provided the game show’s first “answer” more than 55 years ago. At least, that was the case until James Holzhauer took his place behind the podium earlier this year.

After winning 32 consecutive games by an astounding average margin of $64,913 and netting $2.5 million in prize money, one question must be asked: had every one of the show’s contestants been playing the wrong way?

Perhaps. Indeed, Holzhauer, “a professional sports gambler from Nevada,” may have shown the world what’s possible when a player template—never challenged or questioned over a half century—is blown up and replaced by another strategy that produces vastly superior results.

By now, millions of Americans are familiar with Holzhauer’s unorthodox Jeopardy! strategy. It’s actually quite simple: unlike 99.9 percent of the game’s previous contestants, Holzhauer starts at the bottom of the board—where the biggest money is—and goes sideways.

“It seems pretty simple to me: If you want more money, start with the bigger-money clues,”Holzhauer explained in an interview with Vulture magazine. He told NPR, “What I do that’s different than anyone who came before me is I will try to build the pot first” before seeking out the game’s Daily Doubles.

From there, he “leverages” his winnings with “strategically aggressive” wagers (read: wagers far larger than any contestant before him was willing to make).

This strategy—along with the fact he’s answering 96.7 percent of the clues correctly—has allowed Holzhauer to build insurmountable leads heading into Final Jeopardy.

With overwhelming leads, he can be ultra-aggressive with his Final Jeopardy wagers—one he made amounted to $60,013. It was that wager that allowed Holzhauer to establish his current all-time record total of $131,016. (He now holds the top 12 all-time records for one-game winnings.)

After 22 episodes, Holzhauer had earned $1.69 million. Given that each show takes about 24 minutes to play, he was averaging $192,045 an hour.

25,000 previous contestants eschewed this strategy ….

How could a strategy that really is “pretty simple”—one that on a per hour basis generates more income than any job in America—have been eschewed by approximately 25,000 previous contestants?

There are several possible answers to this question, none of which speaks particularly well of America, or Americans.

One is that most people are afraid to challenge the conventional wisdom. If something has been done the same way for decades by everyone, no one thinks that it can be done differently.

That’s especially true if those who do challenge the status quo aren’t celebrated but excoriated.

Holzhauer’s contrarian approach to Jeopardy! has clearly rubbed many Americans the wrong way.

Washington Post columnist Charles Lane labeled him a “menace” who is guilty of violating the “unwritten rules of the game,” a view endorsed by CNN host Michael Smerconish.

Other pundits have accused Holzhauer of using tactics that are “unfair.” He’s been called divisive, polarizing, and controversial, someone who has “destroyed the quaintness of the game” and given America “deadly dull television.”

Some speculate that he’s “gaming the system,” perhaps even cheating. Message board posters have pledged to boycott the show until the “robotic” Holzhauer is defeated.

Thankfully, the opposite view—held by slightly more Americans, if message boards are a gauge—is that James is a sensation whose accomplishments should be celebrated. According to one story, he’s the “man who solved ‘Jeopardy!’”

Another depressing possibility is that the overwhelming percentage of Jeopardy contestants (and, symbolically, the population writ large) is incapable of contrarian analysis or of approaching a problem or puzzle in a unique way.

Americans have either known for decades that the game was being played the wrong way but were too chicken to play it correctly, or James Holzhauer is the only American who’s figured the game out.

It’s too soon to tell whether future contestants will emulate Holzhauer’s strategy. For what it’s worth, over the past two weeks, 16 contestants have competed in Jeopardy’s “Teacher Tournament” and every contestant has reverted to the game’s normal style of play. Such is the enduring power of conformity, of conventional wisdom.

What if conventional wisdom is wrong?

But what if the conventional wisdom is wrong? And how often is it wrong?

According to Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson, the answer is “almost always.”

Samuelson wrote an important if largely overlooked book on this very subject in 2001. The book’s title: Untruth: How The Conventional Wisdom is (Almost Always) Wrong.

Samuelson’s thesis is that people and organizations with an “agenda” often create problems that are either exaggerated or not problems at all. And the solutions policymakers give us to resolve these “crises” typically make things worse.

One can take his premise and run with it. Examples of when conventional wisdom has been wrong are abundant in the fields of science, health, economics, and education. We see it in our aggressive war policies overseas. We see it in our approach to presidential politics, at least before Donald Trump “broke” it.

At this level, disproving the postulate that there’s only one way to play Jeopardy! might not seem like a big deal. It could be, however, if it opens the floodgates of independent thought among Americans.

The great hot-dog-eating breakthrough …

Interestingly, as I was researching Holzhauer, I was able to identify one of his sources of inspiration.

“Do you follow hot-dog eating?” Holzhauer asked a reporter with Vulture who questioned whether he had “broken” Jeopardy!

“No. Can’t say I do,” the interviewer responded.

Holzhauer: “About a decade ago, nobody ever thought someone could eat more than, like, 25 hot dogs in ten minutes. But this guy named Takeru Kobayashi came along and he shattered the record by so much that people realized there was a new blueprint to do this.”

So it wasn’t Secretariat winning by 31 lengths, or Bob Beamon breaking the long-jump record by almost 22 inches, or Wilt Chamberlain scoring 100 points in an NBA game who transcended what everyone thought was possible. Those athletes were simply doing the same things they’d always done, just far better than others.

The story of a 130-pound Japanese man with the goal of eating a mind-boggling number of hot dogs is what cracked the code.

Through intense study and trial-and-error experimentation, Kobayashi discovered two techniques no previous hot dog-eating champion had ever used. He quickly concluded that not only could he beat their records, he could blow them away.

He found that if he ripped the hot dog in two, squeezed each piece into a ball, dipped the balls in water (thereby breaking down the starch), squeezed out the excess water, and tossed each ball into his mouth, his stomach could tolerate many more dogs. The game-changing innovation helped Kobayashi double the existing record his first time out.

But here’s the kicker, one that offers hope for the world. Once Kobayashi smashed the record, his fellow competitors didn’t quit. They didn’t demand that the rules be changed. They simply adapted their techniques and raised the level of their game. Today, an American once again holds the hot dog-eating record—72 wieners in 10 minutes!

The lesson is as obvious as Kobayashi’s bulging abdomen. When someone does think outside the box, when someone proves that performances once thought impossible are in fact obtainable, new levels of excellence become reachable.

When (and if) cancer is finally cured …

When (or if) cancer is finally cured, my wager is it will be thanks to someone like James Holzhauer or Takeru Kobayashi. It will be someone who looks at all the work that’s come before him and says, “This doesn’t make sense. There’s a better way to approach this.”

Over the last two months, Holzhauer has been trying to teach Americans that eye-opening accomplishments are possible if one ignores or rejects conventional wisdom. The more Americans who absorb that lesson, the better.

“I’d be interested to see if there was a new paradigm in [Jeopardy!],”Holzhauer told Vulture. “If someone comes along and breaks my record, and attributed it to my style, that would be really great.”

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Other notable mavericks who revolutionized their sports …

In follow-up articles to my James Holzhauer story, I cited several examples of other “contrarians” who revolutionized the way different activities are performed. Since I’m a long-time sports fan, I focussed on the world of sports or competitions …

Dick Fosbury - The inventor of the “Fosbury Flop” high-jumping technique. Fosbury won the gold medal at the 1968 Olympics using a back-first jumping technique nobody had previously used. Within approximately six years, every competitive high jumper in the world was using the “Fosbury Flop” - and routinely clearing heights previously thought impossible.

Pete Gogolak, who was drafted by the Buffalo Bills in 1964, is considered the first “soccer- style” field goal kicker. Today, of course, every field goal kicker uses this style of kicking.

Notably, the percentage of field goals attempts made has increased from 50 to 60 percent pre-Gogolak to more than 80 percent in today’s NFL. Also, field goals of 50 yards or more, once a rarity, are now routinely made by the best kickers. For more than five decades, every kicker was using the wrong technique.

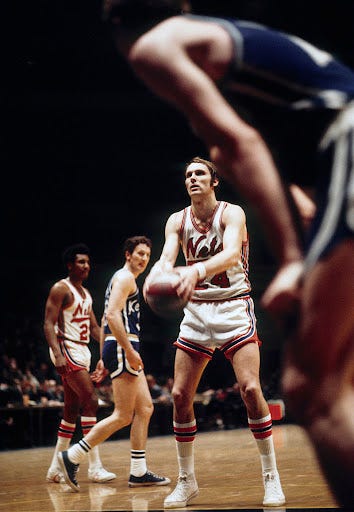

Rick Barry - Barry’s career free throw percentage in the NBA (90 percent) is among the highest in NBA history. As older sports fans no doubt remember, Barry shot free throws under-handed or “Granny style.”

Barry’s “contrarian approach” is noteworthy because, despite his proven success, few if any basketball players utilize the same technique. (The same thing’s happened on “Jeopardy!” where no contestants are playing the game like Holzhauer did).

Another anecdote seems to prove terrible free throw shooters would benefit greatly from adapting the technique made famous by Barry.

Wilt Chamberlain, who holds the records for most points scored in a game and season, shot only 50.4 percent from the charity stripe over his professional career (meaning his scoring records would have been more mind-boggling if he was close to an average free throw shooter).

In the 1961-62 season, Chamberlain set the record for most points in a game (100) and a season (50.4 points per game).

In that season, Chamberlain utilized the “Granny Style” technique for most of the year. Indeed, when he scored 100 points, he made 28 free throws in 32 attempts - an 87.5-percent conversion percentage.

For the season, Chamberlain shot 61 percent from the charity stripe - an improvement of almost 11 percent over his career numbers.

Alas, Chamberlain abandoned the technique because he thought it made him look “silly” and finished his career shooting 48.7 percent from the free throw line.

(Shaquille O’Neal was another terrible free throw shooter who also refused to try the underhand technique because he thought it would make him “look like a sissy.”)

Golfer Bryson DeChambeau might also deserve mention on this list as he uses at least 10 novel approaches to playing his sport and has experienced notable success in his career.

These anecdotes seem to prove athletes (and people writ large) won’t try certain new approaches … even if they are proven to work.

The free throw and medicine examples reinforce the psychological and sociological power of “remaining in the herd.” Or that very few people possess the self-confidence to be a maverick or “think outside the box” and try a different approach.

However, a few examples from sports and game shows prove that when someone does employ a different approach, eye-opening improvements in performance or “results” are indeed possible.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Troy men take care of Southern Miss

In a game moved to Monday because of last week’s snow, the Troy Trojans took care of business at home, beating conference rival Southern Miss 70-61 in front of an announced crowd of 2,400 at Trojan Arena.

Guard Tayton Conerway, who has been on a tear lately, scored 17 points and added three steals for the Trojans (13-7, 6-3 Sun Belt Conference).

Thomas Dowd scored 15 points while shooting 4 for 8 (4 for 7 from 3-point range) and 3 of 3 from the free-throw line and added nine rebounds. Theo Seng shot 3 of 5 from the field and 3 for 4 from the line to finish with 10 points, while adding six rebounds.

The Golden Eagles (9-12, 4-5) were led in scoring by Denijay Harris, who finished with 21 points, seven rebounds and two blocks.

Troy plays Georgia Southern at home on Thursday. Tip-off is slated for 6 p.m.

The game will feature a halftime “Paper Airplane Toss” presented by MGM Regional Airport - an opportunity for a fan to win free airfare. The closest airplane will win the prize. Paper airplanes available at the entrances to enter into the contest.

On Saturday (“Mike Amos Day”) Troy will host ULM in a game that tips at 3:33 p.m.

****

(Thanks for considering a subscription - free or paid - to Alabama’s only “Substack newspaper.”)

loved the history review! Who didn’t enjoy watching James !

Correction: The story says James Holzhauer "netted" $2.5 million on "Jeopardy!" That's wrong. That's the figure he "grossed" before the State of California and Uncle Sam took their tributes.

I think the California State income tax is 12 percent for people who make as much as James did. He had to pay it, because he "worked" in California for six or seven days when the episodes were taped.

Fortunately for him, he lives in Nevada, which doesn't have a state income tax. If he'd lived in New York, he would have had to pay California 12 percent, New York 10 percent and Uncle Same about 40 percent. He also had to pay for his travel expenses and lodging and meals while in California (unless producers pay some kind of per diem for contestants).